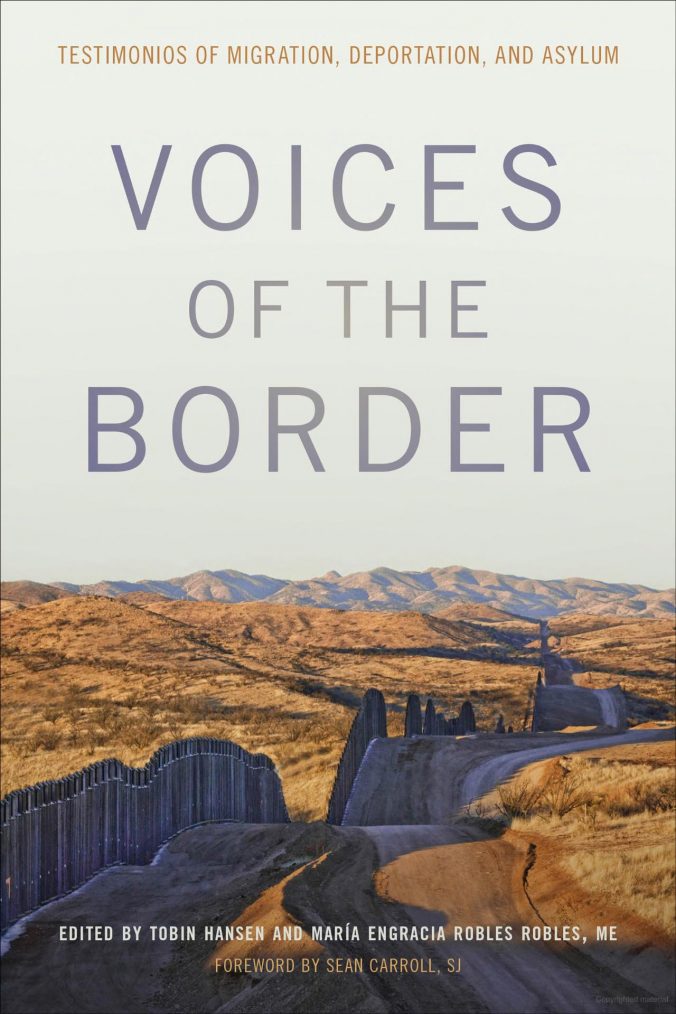

Voices of the Border:

Testimonios of Migration, Deportation, and Asylum

Edited by Tobin Hansen and María Engracia Robles Robles

239 pp. Georgetown University Press, 2021

Reviewed by Phil Boonstra, SJT Immigration Leader

Who gets to tell your story? This is a question that comes to mind while reading this collection of first-hand stories of migrants’ travels between Central and South America and the United States. If you strip away the news’ abstract descriptions of these persons (“migrant caravan”) and go past the legal euphemisms (“Migrant Protection Protocols”, better known as “Remain in Mexico”), then what’s left is what’s in this book: the humanity of the people living through these circumstances. Each testimonio is a first-person retelling, both in the original Spanish as well as an English translation, and thus forces the reader to reckon with the speaker’s experience rather than our own explanations or assumptions.

The testimonios are all from persons who have, over the past 10-15 years, spent time in the cities of Nogales, Arizona or – just across the border – Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, home of the Kino Border Initiative, a migrant advocacy organization. Some migrants traveled from Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, or farther south and were in limbo, waiting for the right time to cross into the US. Others were sent to this Mexican town from the US, deported after a few days or many years of living here. The book is organized around eleven different themes, including wealth inequality, organized crime, gender violence, family separation, governmental abuse and corruption, and migrant criminalization and deportation. Every chapter opens with some contextual information related to the theme and then gives the testimonio of two or three persons.

In each testimonio, the reader encounters a variant of the same paradoxical circumstance, in which the speaker had come to the conclusion that the best and safest option was to leave home, livelihood, and family and traverse hundreds of miles, subjecting themselves to risk of extortion, robbery, or sexual assault. From our perspective, this is unfathomable. Yet, each story shows that, indeed, it is the perfectly logical choice. In a haunting and – sadly – typical testimonio, Julieta Payán Urías shares about her childhood in Mexico City, writing that her children’s father began stalking her at 12 and repeatedly sexually assaulting her throughout her teenage years. Héctor Arturo, a father of two and a deep-sea fisherman from El Salvador, writes about being forced to give fish to local gangs, until such a point as he could no longer feed his own children. Upon refusing to give them any more, they beat him with an aluminum bat. They hunted him across the country until he fled to Mexico, alone.

The testimonios are not just about the circumstances that forced them to flee their home but also their encounters with gangs, cartels, and law enforcement during their journey. Rogelio Heriberto Montes de Ruiz shares about his encounter with US immigration officers upon jumping the border wall at Nogales: “One of them told me to put my hands on my head. I obeyed him. But just then, another one of them coming from a different direction ran at me and gave me a knee in the ribs on my right side…He knocked me to the ground with that knee. I couldn’t breathe” (p111).

Reckoning with such suffering, the reader is tempted to fall back on some variant of legalism (“why don’t they come here legally?”) or nationalism (“countries have borders for a reason”). And yet, these excuses fall short. These people have the legal right to have their asylum case heard without being treated as criminals. And an appeal to nationalism fails to recognize that US military and counterintelligence activities and US corporate expansion in these Central American countries have contributed or even directly led to the problems they are facing today (see Chapter 2 for more details). There are no easy responses here, and this book doesn’t purport to offer any. Rather, it seeks to illuminate and educate. As its penultimate sentence states, “[p]eople need to better understand the situation of those migrating, being deported, or seeking asylum in order to envision a world in which all people enjoy greater opportunity” (p197).

Recent Comments